Shopping for America

Teens boost sales despite wartime woes

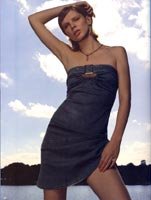

Dressed in a camouflage T-shirt, cargo pants and black high-top Converse sneakers and armed with a wallet full of cash, 15-year-old Sarah Miller is prepared to go shopping.

As she tours an upscale Orange County mall, she exudes pure attitude with a nostalgic rock ’n’ roll patch on her jacket and a silver ring in her nose.

Miller and countless legions of other teenagers refuse to stop shopping, even as the U.S. war with Iraq has curtailed overall retail spending.

That has surprised many analysts who predicted the nation’s malls—where teens usually congregate to socialize and which could be targets for terrorist attacks—would be hardest hit by the post–Sept. 11 economy.

Deborah Downing, marketing director at South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa, Calif., said business has been very strong for retailers that specialize in teen apparel.

“We haven’t noticed a falloff in traffic or sales,” she said.

Any slowdown in teen spending at retail is hardly noticeable, said Tony Cherbak, an analyst at Deloitte & Touche in Costa Mesa.

“Retailers realize the spending power of the teen market and have found ways to make the shopping experience more pleasant for teen shoppers,” he said. “That’s been a very positive step for retailers.”

Cherbak said he is not surprised by the staying power of the teen market. He also said juniors-apparel retailers are less likely to feel the crunch than other segments of retail, such as appliances and electronics.

“Teens have not changed their shopping patterns as a result of conflicts in the Middle East,” he said. “Teens may be aware of wartime activities in the Persian Gulf, but they’re not really connecting to it.”

But Southern California apparel businesses are not relaxing yet—particularly if 2003 shapes up to be like last year. Teen spending in 2002 dropped 3.7 percent to $20.9 billion, according to Marshal Cohen, an analyst at NPD Fashionworld, a market group that tracks apparel sales. Meanwhile, ’tween shoppers between the ages of 7 and 12 spent only $10.1 billion in 2002—4.6 percent less than they did in 2001.

“What we’re witnessing is a major shift in the teen consumer’s behavior,” said Cohen. “Teens are basing their purchases more on need than the pleasure factor.”

The challenge for juniors retailers now is to upgrade their products and add the level of sophistication coming out of today’s youth culture to their offerings, said retailer Shaheen Sadeghi, who owns the Lab Anti-Mall and The Camp, both in Costa Mesa.

“We have a very powerful middle ground, and the level of sophistication has stepped up quite a bit,” Sadeghi said.

The Lab caters to an eclectic mix of teenagers with a variety of stores, including Urban Outfitters, Stateside, Habit and Electric Chair. According to the Lab’s 2002 sales figures, retailers at the complex reported sales as high as $550 per square foot. According to Sadeghi, some malls average only $250 per square foot.

In fact, many local retailers—particularly those that specialize in action sportswear and edgy apparel— are still reporting strong sales in the juniors market.

Pacific Sunwear is one example. The Anaheim, Calif.–based company reported its same-store sales in March had increased 9.5 percent from the same period last year and its total sales to date for fiscal 2003 had increased 21.2 percent since the same period last year.

“As a teen retailer, we believe the youth market is quite resilient to economic problems–– they’re not caught up in the world news,” said Debbie Shinn, vice president of juniors at Pacific Sunwear.

However, not all juniors retailers are faring so well. Guess, Wet Seal and Charlotte Russe have reported downturns in same-store sales for the first quarter of 2003.

For example, San Diego–based Charlotte Russe Holding Inc., which offers private-label juniors apparel and other juniors brands at its Charlotte Russe and Rampage stores, is projecting a decline in comparable-store sales of approximately 11 percent to 12 percent for the quarter ending March 29. Recently, the company also announced plans to close 10 stores.

Scrambling to meet demand

At the manufacturing level, juniors manufacturers that have the inventory to meet the unexpected demand are in a good position. Several local juniors retailers anticipated a downturn in teen spending before the holidays and postponed, reduced or even canceled orders. But the teen market showed no signs of slowing down, and many retailers were soon scrambling for refills.

Juniors-apparel manufacturers said shorter lead times and quick refills are crucial to business. Los Angeles–based Bubblegum USA, which employs roughly 200 workers in the city, produces most of its juniors apparel in China. However, the company keeps an apparel reserve of several thousand units “just in case.”

“Doing business that way can be risky for some, but it works for us,” said Ken Spiegel, chief operating officer and president of sales at the juniors- apparel maker. Spiegel said he has several retail accounts looking to refill orders for miniskirts because they did not order enough during the holiday season for March deliveries.

“To be a great manufacturer in today’s economy, you have to be able to anticipate the success of your trendy items and buy accordingly,” Spiegel said. “We have a tendency to ship early against our start date. We’re getting a good response to that at retail and we’ve been fortunate to see some reorders against the early Spring product.”

Shorts, capri pants, and short and mid-length shirts have been strong sellers for the company, Spiegel said.

“Girls are out there buying true Spring product right now,” he said. “Part of that is we consider ourselves forward thinkers when it comes to fabric. We’ve been doing nicely.”

Los Angeles–based juniors- apparel maker Hot Kiss has a 30,000-square-foot warehouse in Vernon, Calif., which is stocked up on trendy items for quickturn deliveries. The move to create an apparel reserve has saved the company a lot of time and frustration, according to Hot Kiss Vice President of Sales Ben Kaczor.

Hot Kiss’ retail accounts report a sell-through rate of 18 percent each week, and there are already 15 percent to 20 percent more Back-to-School orders than during the same period last year, said Kaczor. The company projects sales of $50 million by the end of the year.

Irvine, Calif.–based juniors-sportswear maker Mak Fashions is another company that likes to plan ahead. The 2-year-old cut-to-order juniors-apparel maker said it keeps an abundance of fabric close by for speedy cut-and-sew send-outs. During these troubled economic times, there is a certain level of risk involved for manufacturers who cut to order, according to owners Marisa and Brad Kenson.

“The effect of war is very short-term,” said Brad Kenson. “What the teen market is experiencing is a hangover effect of a slow economy. The dollars are out there, but the teens are being more selective— basically, we have to serve up a more compelling reason for them to part with the $20.”

So, what are the styles teens can’t resist?

Military-inspired jackets, pants and shirts with zipper trims, loopholes, badges and patches; “Grease”- inspired, satin baseball jackets; plaid miniskirts; nostalgic T-shirts; mesh tops with studded-leather details; rubber bracelets; Converse tennis shoes; and anything to do with Avril Lavigne, according to Barbara Fields, a Los Angeles–based trend forecaster and owner of the Barbara Fields Buying Office.

“The war has affected the psyche of everyone, but not so much in the teen market,” said Fields. “They have that disposable income, so they’re not as affected.”

But that may change soon. Wet Seal Senior Vice President of Marketing Steven Strickland said teens’ spending is tied to their parents’ wallets. Earlier this month, the Foothill Ranch, Calif.–based retailer conducted a series of teen focus groups in New York, New Jersey, Illinois and California.

According to Strickland, many teens under the age of 17 complained about their parents cutting back on—or cutting out—their allowances, and teens over the age of 15 said their parents were telling them to get a job.

“Some teens were very upset when they told me their parents were telling them that if they wanted something, they had to buy it themselves,” Strickland said.