Inviting Competition

The struggle is worth it on hot retail streets, L.A. boutique owners say

It’s a calculated real estate risk.

Retailers who opt for a boutique on crowded streets are hoping to capitalize on the area’s heavy consumer traffic. But they also risk losing sales to other retailers in the neighborhood.

This is the gamble many entrepreneurs take when they open fashion boutiques in areas with the reputation of being on a “hot” street.

In the past two years, more Los Angeles real estate has been anointed with the sizzle of being a hot retail street. Boutique owners on streets such as Robertson Boulevard or Melrose Avenue report a lot more competition with every wave of new fashion stores––from nameplate stores that sell products from international fashion companies to independent boutiques looking for a piece of the city’s retail pie.

Boutique owners often say hot locations have their drawbacks from skyrocketing rents to maintaining exclusives on fashion brands. But many retailers say the resulting surge in retail traffic makes the trade-off profitable.

Neely Shearer, co-owner of contemporary boutique Xin has sold emerging contemporary designers for more than seven years at her boutique in Los Angeles’s Melrose Heights neighborhood. For many years, Xin, Fred Segal and Madison were among the only fashion boutiques on the block. Yet in the past 18 months, the store’s intersection of Melrose Avenue and Crescent Heights exploded with interest from the fashion industry.

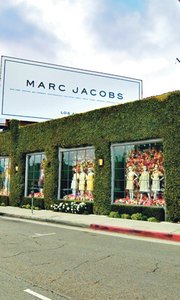

Branded stores from fashion companies such as BCBG Max Azria, Adidas, Paul Frank, Original Penguin and Antik Denim have opened in the past year in the area. They followed a designer invasion of Melrose Avenue west of Fairfax that included the highly anticipated boutiques of fashion icons such as Marc Jacobs, Paul Smith, Diane Von Furstenberg and Carolina Herrera.

“Even if the economy is not perfect, we see a lot more new faces along with longtime customers,” Shearer said. “It’s because the area has become a destination.”

In addition to Robertson and Melrose, Los Angeles has seen an expansion in its fashionable neighborhoods, including West Third Street and La Brea Avenue. Demand is so high that entrepreneurs are sniffing out other thoroughfares that may have the potential to be hot, such as Pico Boulevard or La Cienega Boulevard adjacent to Melrose, according to Carol Chait, a real estate saleswoman with Los Angeles–based Stafford Commercial Real Estate.

“The rent goes up just before your very eyes,” Chait said. Prices range from $7 to $8 per square foot on her neighborhood turf — the 8500 block of West Melrose Avenue. Rates for commercial real estate in Los Angeles County have increased 50 percent since 2001, according to Delores Conway, director of Casden Forecast, a service of University of Southern California’s Lusk Center for Real Estate.

The rapid rise has veteran retailers such as Fred Levine worrying about how new entrepreneurs can start a boutique and be successful. “The cost of doing business is too high in retail,” said Levine, who co-owns more than 20 M.Fredric stores in Los Angeles County. “The sweater that cost $120 this year cost $90 a few years ago. But the costs of rent and payroll doubled.”

The only way to beat the costs is to sell three times as many sweaters, according to Levine. “Staff and inventory has to be lean and mean,” he said.

According to Alison Muh, president of Los Angeles–based accessories brand Surly Girl, opening a store might be the only route to building one of the brass rings of the fashion industry: the lifestyle brand.

She opened her boutique, Surly Girl, on the 100 block of North Robertson Boulevard more than 18 months ago. It shares Robertson’s concrete with celebrity stores such as Lisa Kline and Kitson. “It’s absolutely saturated,” Muh said of the market for boutiques. “But if you want to be a big brand, you have to get into retail. Kate Spade and Juicy [Couture] both do it for a reason.”

Muh said once a lifestyle brand gains success, it should remain successful. “There will always be girls who want to be Juicy girls,” she said.

Nanette Lepore also believes that opening a boutique on Robertson was crucial to the success of her self-named fashion brand that’s based in New York. While a multi-line retailer might not display an entire line, a branded store can serve as a showroom for the label where every style a manufacturer produces can be displayed.

Yet opening a store holds a price for manufacturers. They can lose business they already have on the street when their boutique opens. For some the risk becomes the reward. Before she opened her Robertson boutique, Lepore’s brand earned $100,000 from being sold on the shelves of Robertson boutiques Kitson and the now defunct Cosa Bella, according to the designer’s estimate.

When she opened her store in 2002, she lost her Robertson accounts, but she said that she now earns $2 million annually from her Robertson boutique.

Los Angeles has long been a haven for boutiques, but that’s not necessarily the case outside the Southern California region.

There might be a saturation of retail centers nationwide, but there’s still a shortage of boutique neighborhoods across the country, according to Shaheen Sadeghi, president of The Lab and The Camp shopping centers in Costa Mesa, Calif.

Larry Kosmont, a real estate analyst for Los Angeles–based Kosmont Companies, argues that retail for shopping centers will never be oversaturated. The market will always have growth potential as long as the population is growing, he said.

But Sadeghi counters that boutique neighborhoods can become flashpoints for a city’s personality.

“People are looking for cool neighborhoods with boutiques,” said Sadeghi. “It creates a lot of value for the community. These neighborhoods become places where people want to live, work and entertain.”