UCLA Anderson Forecast Predicts the Fallout from ‘Trumponomics’

As of Thursday, December 8, 2016

UCLA Anderson economists got caught by surprise when Donald Trump was elected to be the 45th president of the United States.

They believed that Hillary Clinton would be in the White House when they put their forecast together in September.

For their end-of-the-year forecast, the economists at the UCLA Anderson School of Management went back to their crystal balls and sketched a different economic scenario for 2017 and 2018. That economic outlook, the UCLA Anderson Forecast, was released on Dec. 6, highlighting the economic differences between Trump and Clinton.

“Clinton was going to raise taxes, essentially, and spend more. Trump is going to cut taxes and spend more,” said David Shulman, senior economist with the UCLA Anderson Forecast, noting the differences between the two politicians.

Shulman believes that Trump will implement a personal tax cut for higher-wage earners that will total $300 billion a year, impose a $200 billion a year corporate tax cut, push for a $20 billion–a–year infrastructure program going into effect by the end of 2017, seek a $20 billion–a–year cut in Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, and make modest changes to trade policy that will lead to net reductions in food and aircraft exports.

“With $500 billion in tax cuts arriving in the third quarter of 2017, we expect economic growth to accelerate from the recent 2 percent growth path to 3 percent for about four quarters,” Shulman wrote. “Thereafter, growth will slip back to 2 percent.”

GDP will eventually slow down because the economy will need a productivity miracle to continue to stimulate growth. “Whether that will come, as the Trump partisans expect, from the supposed supply-side effects of the tax cuts and the proposed regulatory reforms remains to be seen,” Shulman noted.

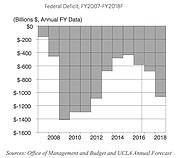

Shulman predicted that Trump’s take on the economy will lead to the federal deficit doubling to more than $1 trillion by 2018, which in the long run will pose a problem when the government needs more funds to pay for Social Security and Medicare.

With an exploding federal deficit and a higher inflation rate, the long-quiet Federal Reserve will become more aggressive and raise the federal fund rate to more than 2 percent by the end of 2017 and to 3 percent by the end of 2018.

Trump will have a bigger influence over the Federal Reserve after he takes office because there are two vacancies to fill on the seven-member Federal Reserve board, and Janet Yellen, the Fed’s chair, will see her term expire in January 2018. “Trust me, we will have a much different Fed under President Trump,” Shulman noted.

With that in mind, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is forecast to exceed 3 percent by the end of 2017 and 4 percent by the end of 2018.

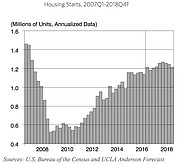

But mortgage rates are also going up, which means fewer houses will be built. Shulman predicts that instead of the previously forecast 1.4 million housing starts per year for 2017 and 2018, that should be reduced to 1.2 million to 1.25 million housing starts.

With a better economic outlook, the nation’s unemployment rate is expected to dip from its current 4.6 percent to 4.5 percent by the end of 2017 and remain there through 2018.

Because of a tightening labor market, wages will grow about 4 percent or more starting from the middle of 2017.

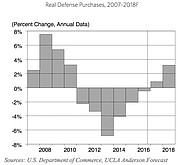

With Trump expected to increase the United States’ presence in the Middle East and elsewhere, the government’s defense spending should start rising after declining for six years in a row. The expected spending uptick in 2017 is 0.8 percent and 3.2 percent in 2018. That bodes well for California, which has several aerospace companies and aircraft manufacturing in Los Angeles and San Diego.

“The increase in defense spending will be disproportionately directed to California, as sophisticated airplanes, weaponry, missiles and ships require the technology that is produced here,” wrote UCLA economist Jerry Nickelsburg. “Regionally, we expect a positive impact in the Bay Area and in coastal Southern California.”

The forecast for total employment growth in California is 1.8 percent in 2017 and 1.3 percent in 2018. Payrolls are expected to grow at about the same rate. Despite its 5.5 percent unemployment rate, the state is just about at full employment. “Where the state will find people to fill new jobs remains to be seen as the new administration is expected to oppose an expansion of the skilled-worker visa program,” Nickelsburg wrote. He noted that rising wages for skilled workers would probably induce employees from outside the state to move to California.

Nickelsburg said employers in the Central Valley region of California’s agricultural sector should worry about Trump’s threat to deport undocumented workers. “It’s estimated that as many as half of California’s farm workers are undocumented,” he said. “If these workers are deported, California’s farmers will have trouble harvesting their crops while paying much higher wages to their documented farm workers.”

In a silver-lining-in-every-dark-cloud kind of philosophy, Nickelsburg noted that about 22 percent to 26 percent of undocumented workers live in California, which means with some immigrants being deported, there will be less of a housing shortage.

He noted that home building will continue in California at a rate of about 120,000 units per year.