The World’s Smallest Shoe Factory Introduced to FIDM Students

Technology

As of Thursday, May 2, 2019

Since its launch in 2003, shoe brand Keen Footwear has sought to change the market and become a force for good in the world. It is famous for its “Newport” sandal—an active footwear style designed with a reinforced toe—and it continues to search for new innovations.

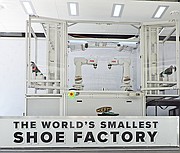

Keen’s most recent project has been working with Uneekbot, called “The World’s Smallest Shoe Factory.” Over a two-year period, the machine was developed by a 17-year-old engineer named Oscar Williamson and programmed by House of Design, a robotics system-integration company in Idaho.

At a cost of $300,000 per machine, Keen invested in three Uneekbots—located in Japan and at the company’s headquarters in Portland, Ore., with a third being built for the Netherlands location. On April 10, the company arrived at the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in downtown LA as part of its nationwide tour introducing Uneekbot to schools and companies aboard a solar-powered trailer.

“Ultimately what we would like to be able to do is have the machine in the store. The customer comes in, punches in the colors that they want, the size, the style and sits there and waits eight minutes for a pair of shoes,” said Chris Brown, design director of outdoor performance for Keen Footwear. “It’s like an automated vending machine.”

The dual-arm robot is able to manufacture one pair of Uneek sandals in eight minutes by knitting paracord through a rubber sole. The Uneek slide sandal design being manufactured that day at FIDM will not be sold in stores, but the company is providing pairs for students to try. This exclusive tour style most closely resembles Uneek’s “Monochrome,” a men’s design that retails at $100 and also features a heel and side wing not found on the Uneekbot-created shoes manufactured in sizes 5.5–9.5 for women and 8–12.5 for men.

Keen’s executives are excited about Uneekbot’s potential, but there are still some challenges. According to Brown, Keen’s owner, Rory Fuerst, is known throughout the company as a leader who challenges his team and is fascinated by innovation in manufacturing. With a tentative goal of moving forward with new Uneekbot-manufactured designs within one year, Brown is realistic regarding the obstacles when working with the machine.

“If a cord is just twisted a little bit, the robots are very sensitive to the tension of the cords. So if the tension is not 100 percent correct, it could throw the machine off a little bit,” he said.

The company produces its soles at a Keen-owned factory in Thailand. Its paracord is also made in Thailand, but the company’s project manager, Scott Owen, revealed the goal is to eventually find sources that are located within the vicinity of each robot and can provide materials to regional Keen locations.

“It’s [Uneekbot] really here to showcase a minimalist design and really trying to utilize all the materials for the shoe and not have any waste,” Brown said. “That is key regarding why we’re using a robot. We’re also trying to bring manufacturing back to the U.S.”

One of Keen’s most common shoe-manufacturing resources is its DESMA direct-attachment, injection-mold machine, which molds the shoe’s outsole around an upper, Brown explained. With the Uneekbot, Keen’s team hopes to further automate the process to make shoes.

With the Uneekbot completing 80 percent of the shoe, the remaining 20 percent must be completed by hand. Despite the decrease in the amount of hands required to manufacture each pair of shoes, there will still be opportunities to increase jobs through finishing, machine maintenance and production management.

The Keen collaboration with FIDM started with Owen reaching out to arrange a Uneekbot stop at the campus. The tour has also included visits to the University of California, San Diego; University of Southern California; University of California, Irvine; and Stanford.

Eva Gilbert, who is FIDM’s department chair for merchandising and marketing, believed her production-and-sourcing students would benefit from learning more about Keen’s work with Uneekbot, which fits perfectly into their curriculum.

“They start out in the class taking a picture out of a magazine, and they have to source every component,” she said. “They have to find the material, they have to find the labor, and they have to find the boxes and the bags and the hangers.”

While Keen wanted to reveal its exciting new manufacturing venture through tours, the company also is interested in finding innovative college students. At stops along the tour, Keen is offering internships available only to students whom they meet during the company’s campus visits. Ultimately, Keen will choose five to seven students to join its team during the summer of 2019.

The students who apply must design their own internships, outlining what they can bring to the company during their time at Keen. The internships will pay above minimum wage, with Keen covering housing costs.

In addition to the internship, Keen is hosting a design competition only for students of FIDM and Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland. As the Keen team explores its shoe-making possibilities with the Uneekbot, it wants students to think about how they would design products using the machine. The first-place winner will receive $1,000 and a trip to the company’s headquarters to present the design, with an $800 second-place prize and $400 for the third-place award, which also will include designs being showcased and promoted by Keen.

One of Keen’s latest goals was to increase the recycling rate of its excess materials, which went from 55 percent to 84 percent after one month. As a company committed to producing minimal waste, Keen has found unique ways to partner with other organizations to reduce excess materials that would otherwise end up in a landfill.

“All this extra cord is donated,” Owen said. “We found the Girl Scouts could take it and can use it for tying knots and practicing.”