Building a Green Business Model

From passion to productivity, Indigenous sets an eco example

Lots of people these days talk green. But few have the green credentials sported by Indigenous Designs. For more than a decade, Indigenous has carved out a niche in women’s contemporary, men’s and kids’ handknits and wovens, drawing exclusively on South American artisan workmanship. Indigenous’ grass roots approach to design and marketing has been the subject of case studies. Even the Wall Street Journal and CNBC have taken notice.

With increasing public demand for socially conscious clothing (organic clothing currently accounts for $1 billion in sales, with $5 billion anticipated in the next three to five years), kudos have been accorded Indigenous’ co-founders, CEO Scott Leonard and President Matt Reynolds, who have turned an authentic South American apparel collection into an international apparel business.

Nearly 15 years after the company’s start-up, Reynolds says, “The main reasons we’re still alive are ignorance and endurance. There were huge learning curves.”

It’s been a long road—literally—from concept to the comfortable spot the company’s in today, and nothing seems to fire up Reynolds’ juices more than an opportunity to talk about his business. “We have an incredible passion, Scott and I,” he says, “and we were steadfast in our belief that this is a model that needs to exist and can thrive.”

In the Beginning

Indigenous was founded in 1994, when Leonard and Reynolds, friends from junior high, met up again at a wedding and started talking. Leonard, who owned a Santa Cruz surf shop, was just setting up Indigenous and had spent time in Ecuador, “specifically to set up ways to bring in Ecuadorean sweaters, respecting the lifestyle and artisans of that country,” Reynolds explains.

“I had just come back from Europe, where I had seen a very large demand for fair trade and organic apparel,” Reynolds adds. “I thought there was a tremendous opportunity in the U.S. for emerging-market fair trade and organic product.”

Reynolds, who hails from a family of “economic developers,” spent the better part of his youth living in Central and South America. “Back then, it was all about wanting to find a way to connect directly with artisans and circumvent middlemen, control what knitters would be paid and improve infrastructure and supply side of what they had access to, as well as design skills. That was the first start of the idea,” Reynolds says.

Within days of their reacquaintance, Leonard and Reynolds had formed a partnership—along with a third partner, native Ecuadorean Joe Flood—and they took off for South America, where the search for artisan communities was like a treasure hunt. “Joe had family, and he knew where artisan communities were. He started hiking through the mountain communities to find them,” Reynolds recalls.

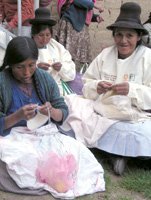

The trio’s travels and quest to find indigenous artistry in Ecuador laid the foundation for its current base of operations in southern Peru, where Indigenous works with 275 knitting groups, each with anywhere from four to 60 artisans, in the areas surrounding the Pampas Cuevas Reserve. The Reserve includes the cities of Arequipa, Lima and Ayaviri, and it also runs a fair-trade organic cotton-jersey factory.

On that initial trip to Ecuador, Flood came across three small separate cooperatives in close proximity that competed for work. Indigenous had a 4,000-unit order. “Not one could have produced the order in time,” Reynolds says. “We had to unify them, work to get them to partner and become one source.” Beyond that very basic step, however, lay years of work and investment—self-funded for the first six years—that now has come to fruition.

The raw, rough fibers and bulky sweater designs the artisans were used to working with were fine with Indigenous’ early outdoor-industry clients such as Nature Company, REI and Adventure 16—retailers who, Reynolds says, were interested more in the story than the fashion element. Leonard and Reynolds had higher aspirations—premium products that could sell in the best department stores and upscale boutiques. “We needed to perfect the fibers, the raw materials, the design, spec-ing—everything needed to be done to perfection,” Reynolds says. “They were already such incredible knitters, but we elevated their skill sets. We taught them to do fully fashioned sleeves, how to read spec sheets, how to follow details down to the T. We invested millions of dollars in infrastructure and countless training sessions.”

In Partnership

The Leonard-Reynolds model is a partnership between the knitting groups and with each artisan. For some knitters, a way of life previously meant knitting with bicycle spokes and bartering sweaters for food. Those days are distant now. Indigenous provides the artisans with free training, a free set of needles, and access to the yarns and designs. Indigenous uses only natural and certified organic fibers such as alpaca, silk and merino wool, organic cotton and Tencel.

It typically takes 12 to 18 months to bring an artisan up to company standards, at which point the artisan is invited to join one of the established knitting groups. The company contracts in advance with cotton farmers to ensure a steady supply of cotton filaments. Indigenous’ four designers work out their styles, relay to the mills what colors to stock, and place the fiber purchase orders. The yarns, now boasting “a hand as soft as cashmere,” are issued to the company’s several management hubs, which are responsible for dividing up and overseeing the work among the knitting groups. The yarns are then made available to the groups, on a type of “loan” basis. As the pieces come in, the cost of the yarn is deducted from the labor cost. “That gives a sense of accountability to every knitter,” Reynolds explains. If the pieces are not up to snuff, the knitter is given instruction on how to correct the problem.

As for labor costs, the price is a result of discussion between the company and the knitters. “We say, ’Here is the design, what is reasonable to be paid for this?’ Typically,” Reynolds proudly says, “we pay a 200 to 300 percent premium above what they would make in the nearest metro cities, like Lima. Because there’s no middleman, we can afford it.”

Hand-held and hand-woven looming is done at facilities where “cleanliness is emphasized.” Indigenous provides the fibers, as well as low-interest loans to upgrade the equipment. “We’ve had electricity go to communities that didn’t have it before,” Reynolds explains, “because they can show the government they are generating gross national product and they have an organization.” The looming is taken in panels to one of the main hubs and hand-linked there, steamed, pressed, tagged and bagged for shipping.

The egalitarian nature of the relationship, along with access to premium yarns and sophisticated training, has ensured Indigenous a steady, skilled work force and a reliable production base. “We are continually the largest source of work for these knitters,” Reynolds says, “yet there is no contract that they have to work for us. We have been working with them for so long, built such a trust, that there is a great bond and tremendous loyalty.”

Back in the early days, Leonard and Reynolds relied for support on “socially responsible business owners like Ben and Jerry and Patagonia,” Reynolds says. “We did a ton of networking, learned from some of the best of the best when to raise money, when not to raise money, when to reach out to majors, when not to, finding financing, creative ways to provide capital to small scale producers when they needed it.” At the beginning, it was tough. “We would do MAGIC, and we would never mention organic and fair trade,” he says. “We sold strictly on the merits of the clothing. Only when we knew people, and they understood, did we tell them. It was never our lead-in.”

A Decade Later

The progressiveness Indigenous has brought to its South America operations translates at home as well. The company maintains an eco-friendly headquarters in Santa Rosa, Calif., purchasing all its power from a local power grid, and employee incentive programs give monetary rewards for carpooling, buying a hybrid car and even replacing the light bulbs in their homes. “[It’s those] little things to make them think about their carbon footprints,” Reynolds explains.

Indigenous sells widely, under its own label and upscale private label collections, through mainstream and eco boutiques, catalogues such as Sundance, spas and resorts, outdoor living chains such as Adventure 16 and REI, national chains such as Whole Foods, Dillards, Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus. The company is on-track to clear between $5 million and $6 million this year—a 55 percent increase in a downturn economy, Reynolds notes.

The goal is much higher. “We’ve learned now to stay laser-focused,” Reynolds says. “We want to hit $15 million to $25 million in this niche. Once we’re there, that’s when the company starts branching out, maybe a home line or furnishings or a spa.

“Where we are working,” Reynolds says, “there is unbelievable talent.”

The Economics of Eco

For those interested in developing product in emerging markets, Indigenous President Matt Reynolds offers some advice:

bull; To really know the consistency and production capacity of a small-scale producer, test them on a smaller scale before going gangbusters. You can look at a beautiful original sample and when production comes get burned. Really do your homework on a group.

bull; If you want to make a difference in an artisan’s life, know where the production is going. Meet the actual artisans, on their own, without a supervisor or middleman. There are a lot of con artists out there.

bull; For organic fibers, make sure you get the organic certification, track it, get dates on it, make sure it is for your yarn. There is a lot of “greenwashing” going on right now.

bull; Ask for audits.

bull; You don’t want to overwhelm an artisan or group in the beginning. Go in and build your infrastructure first, before selling to the majors. If we hadn’t done that, we would have failed.

bull; Make sure you love what you are doing. Without the passion, it will fizzle, because it’s so much work.