San Francisco's Growing Design Hub in Dogpatch

Design and manufacturing find a new home in San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood.

When designers started to find that studio space in San Francisco’s Mission District and Hayes Valley was too expensive, they opted for an unusual choice—Dogpatch, the tiny neighborhood sandwiched between Portrero Hill and the San Francisco Bay, cut off from the majority of the city by the 280 freeway.

Originally named after the dogs who roamed the streets looking for discarded scraps from local slaughterhouses in the 1800s, the neighborhood is an unlikely spot for high fashion with its gritty roots and inconvenient locale. However, the draw was not only cheap real estate but a resurgence of independent artisans and small apparel manufacturers who have sprung up in the area.

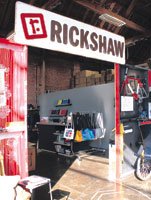

“It has become an entrepreneurial destination, whether you’re making things or designing things,” said Mark Dwight, founder and chief executive officer of Rickshaw Bags and founder of SFMade, a nonprofit dedicated to encouraging local manufacturing in San Francisco.

Dwight opened the doors to his bag company, which is known for its brightly colored customized messenger bags and backpacks, in 2006. Located in an old warehouse, the retail store and factory house a team of 20 employees, including 14 sewers who create built-to-order bags and backpacks that are sold online or through the store.

Dogpatch’s entrepreneurial vibe is part of what drew Dwight to the location.

“There is a lot of activity and a definite sense of creative community—for both designers and makers,” he said.

The American Industrial Center, which serves as a creative and industrial hub for the neighborhood, is located only a few blocks from Rickshaw Bags. Located in an old cannery that has been subdivided into workshops and offices, the center has become a magnet for designers, artists, textile manufacturers and specialty food makers looking for inexpensive studio space and creative camaraderie.

Nice Collective, Piece x Piece and Triple Aught Design are just a few of the apparel companies in the building, which is also home to fashion photographer Stevan Nordstrom. These businesses are supplemented by an assortment of woodworkers, caterers, confectioners, graphic artists and design students.

Dwight said he would like to stimulate an artisanal manufacturing renaissance in the area, specifically dedicated to small manufacturers “for whom local is an advantage.”

Businesses can brand themselves using San Francisco’s distinct lifestyle, natural beauty and history, he said.

By creating a dedicated manufacturing neighborhood, the city encourages the entrepreneurial ethos and small-business growth.

“The old Yankee spirit was ’Let’s figure out how to make it.’ There was value in knowing how to make something, but ’Design it here, make it there’ is the first instinct now,” he explained. “As manufacturing goes, so goes innovation. We’re losing a very important component of our innovation as we’re abdicating manufacturing to the rest of the world.”

With little foot traffic and limited street-level retail space in the neighborhood, Dwight thinks the area will draw more manufacturers than retailers, but wine bars and restaurants have already started to move in, and tours of the Rickshaw Bags factory have become increasingly popular.

Destination for design

“It won’t be a Hayes Valley, but you can still make it a fun destination,” Dwight said.

Janet Lees, director of programs and communications for SFMade, said that one of the most interesting things about the renaissance of Dogpatch is that because of its isolated location, it’s not a walking destination like much of San Francisco. Its draw is its unique collective of artists, makers and culinary specialists.

“People see it as an incubator—a community for them. It’s a creative apparel hub, and there are a lot of start-ups in there,” she said.

Ben Ospital, co-owner of Modern Appeal Clothing (MAC), recently opened a new location in Dogpatch and said retail can prosper in the area.

“Foot traffic is overrated. Being authentic to the client is always better,” he said. “I have been in high-density foot traffic and no-density foot traffic, and it’s far better to be exceptional than convenient.”

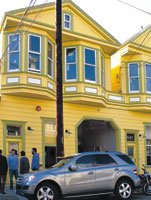

His original store is located in Hayes Valley, which is known as a prime shopping location, but five months ago, he opened the new space on Minnesota Street after hearing about the “symbiotic community” of designers and makers from the owners of Piccino Cafeacute; and Dig wine bar, which are located in the same building as the new MAC store.

“The whole area is booming,” he said. “It’s a neighborhood of creators and artists.”Western Textile, The Podolls and Lemon Twist are just a few of the designers and manufacturers he named as new to the neighborhood.

Ospital said the area is a community of makers that feed off collaboration, which is why he opened a store there.

MAC’s new space is in an old refurbished stable known as the Yellow Building, and it features reclaimed wood floors, fallen poplar fixtures and shelves made of old wine barrels.

“No tree died for fashion,” he joked.

Despite being off the beaten path, the location still receives great foot traffic from the “tribe” of local artists, designers and food workers, he said.

He also draws shoppers interested in supporting his ethical fashion ethos.

“Hands make clothes, and you must respect the hands that made the garment,” he said in reference to cheap, quickly made “fast” fashion, often made under poor labor and environment conditions.

Ospital espouses a slow-clothes movement similar to the slow-food movement, where clothes are made by companies that support more-sustainable production and ethical treatment of workers and the environment. He promotes high-quality, longer-lasting clothes in place of cheap, mass-produced garments and seasonal trends.

“Fast clothes are like fast food—they come from a place of total disrespect. hellip; We vet every vendor. We know the sewers, we know the tailors, we know the fabric in the mills.”

He views his ethos as very much in line with the neighborhood. “It’s more proletariat than celebrity here,” he said.

MAC carries high-end apparel that sports a higher price tag but is ethically made and designed to last for many years. Lemon Twist, McIntosh Fry and Ryan Roberts are some of the California designers the store carries, many of whom are members of SFMade. International labels such as Dries Van Noten, Maison Margella and Kolor are also featured.

Next door to the store is the studio for The Workshop Residence, a program designed to bring artisans and designers from around the world to promote craft, art and design. The program is in partnership with MAC, and goods from the participants are sold at MAC and other retailers. Martha Davis, a shoemaker from New York, was one of the first artists to participate.

In spite of the area’s growing popularity, Ospital said the development doesn’t feel as out of control as it did during the dot-com days, when industrial areas of San Francisco were rampantly taken over by wealthy corporations.

Apparel Arts, a fashion design and patternmaking school located in the American Industrial Center, has been in the area for 15 years and has weathered the ups and downs since the days when Esprit was headquartered nearby.

“When we started in the mid-’90s, a lot of fashion companies and designers and factories and patternmakers were in the area,” said Suzy Furrer, founder and director of the school. “It was very welcoming to apparel, but then start-ups came in and rents went way up for non-lease fashion and art-related businesses, and then the bubble burst.”

Neighborhood apparel design and manufacturing died out for many years until recently, Furrer said.

Old Navy opened its headquarters in nearby Mission Bay in 2006, but there is much more of a focus on artisans, entrepreneurs and new businesses in Dogpatch.

“San Francisco has always had an entrepreneurial spirit—people doing their own thing, getting craftsy,” Furrer said.

She said the area can sustain small businesses well but she “feels the crowd coming” with the development of the Mission Bay UCSF Medical Center and the building of new condos.

The design school teaches 120 to 130 students a month, most of whom are aiming to be in the fashion industry, with only a small handful taking classes for fun. Many of the students wind up renting space in the building to maintain their connection to Dogpatch’s fashion and manufacturing community, she said.

Ospital sees Dogpatch as the perfect spot for a customer revolution that embraces craft and ethics over mass production.

“People want value in their clothes. They’re tired of being marketed to,” he said.